© Ksenia

Ryctycka 2012-2021

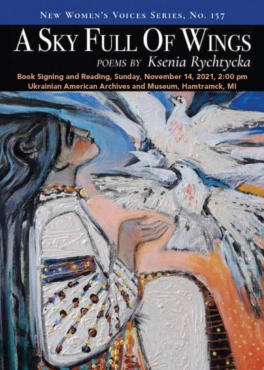

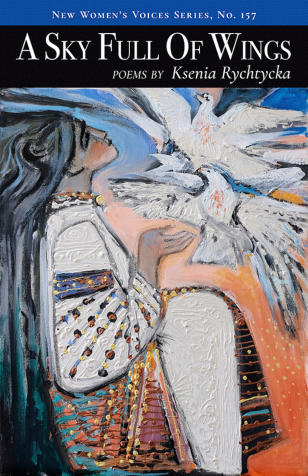

A Sky Full Of Wings

“A Sky Full of Wings is a labyrinthine collection … the poems’ speaker reflects, questions and

explores ancestral ties, ancestral land, family, and the spaces and places that leave the deepest

impressions on one’s being. …At the heart of A Sky Full of Wings is loss. As Rychtycka’s intimate

poems detail her grandparents’ and parents’ escapes from war-torn Ukraine, readers find themselves

encountering a history that history textbooks of the Western variety often ignore. … Hope and

fulfillment, however, conquer the loss and the perpetual sadness of losing one’s homeland. What

readers find throughout the book are poems of return where a single trip reunites one with the

language and a culture with which one is familiar and a part of, but has remained separated from,

due to geography. A Sky Full of Wings is a powerful collection, one that possesses the grace and

history of Lina Kostenko’s work, and is sure to engage readers of all backgrounds and cultures.”

— Nicole Yurcaba, The Seneca Review

* * *

“In Rychtycka’s poetry compilation, the use of vivid sensory images brings the intimate feelings of

one’s memories to life. An ode to journeys past, the poet’s trek ranging from Chicago to Kyiv is eye-

opening, weaving together a snapshot of time that is sometimes torturous and haunting, at others

hopeful and resplendent. ... More than anything else, the compilation uses a raw and authentic voice

to highlight the limitlessness of the skies as they show that however dark a day can get, hope

endures.”

— Mihir Shah, US Review of Books

* * *

“Like the graceful birds bursting forth on its cover, the poems journey through ancestry, family and

geography. From the annals of family history, stories of survival and identity, and the journeys of

finding, losing and reclaiming one’s self will inspire. With a dedicated narrator, readers travel

Chicago, Zagreb and even to Chornobyl. The tug of ancestral homeland enters the beauty of the

Carpathians where towns bear family names and birds of good luck land on Kyiv balconies. Though

loved ones may be gone, they are not out of reach, for they are only a memory away.”

—Eric Hoffer Book Award

* * *

“Both a sojourn that connects modern-day America with family roots in another culture and an

inspection of evolving values and new experiences, A Sky Full Of Wings embraces the heritage of

grandparents who left everything behind to journey to America, and a mother who returns to her

native land in 1990 after fleeing the old world:

With Father, Mother danced the tango, fast/as gunshots once chasing her across Europe./

Here, mother treads slow — pointed toes/and stiffened arms — relearning first steps/on native soil.”

—D. Donovan, Senior Reviewer, Midwest Book Review

* * *

“Although this is Ksenia Rychtycka’s first poetry collection, A Sky Full of Wings is a masterful

work, showing her mastery of the free verse genre. This book explores many important themes,

including dealing with evolving family relationships, exploring Ukraine’s history and current

political reality, and coming to terms with the human cycle of life and death. Ukrainian readers will

definitely relate to images of their childhood, their history and their community. Other readers will

be captivated by the beautiful imagery and skillful literary technique displayed in her poems.”

—Myra Junyk,

Knyzhka Corner Book Review

Nash Holos Ukrainian Radio

* * *

“The poems that make up A Sky Full Of Wings carry readers on a journey rich with longing and loss,

with the elation born from first steps, first love and bright, new surroundings. In this haunting

collection, the journeys are physical and psychological, joyful and poignant such as the revelations

that come in Poem For The Child Who Doesn’t Speak: On the trampoline you are poised like a

bird/…Our eyes meet/and then you rise higher than I can reach/my arms cradling only air.

Heartbreaking and healing and deeply life-affirming, this collection soars.”

—Laura Bernstein-Machlay, author of Travelers

* * *

“The poems of a true inheritor: watchful, quiet, life-stunned: heavy and alive with beauties and

sorrows both present and past.”

—Olena Kalytiak Davis, author of four books of poetry,

including The Poem She Didn’t Write And Other Poems

* * *

“Like the birds that permeate her evocative poems, Ksenia Rychtycka crisscrosses the ocean from

Detroit to Ukraine as she guides us through the sinuous paths of her journey from childhood to

present. With a feather-light touch that reaches immeasurable depth — through stories of four

generations of her family — she honors centuries of the turbulent history of her native land. Along

the way, she invites us to see this earth which has molded her, feel this wind that has carried her,

embrace the rain that has opened each fragile bud and washed away pain and sadness. She has

opened her heart.”

—Myrosia Stefaniuk, author of Dibrova Diary

© Ksenia Rychtycka 2012-2026

Cover Artwork: Edward (EKO) Kozak,

News From Ukraine, Oil on Canvas

Cover Photo: Maria Bologna

Cover Design: Finishing Line Press

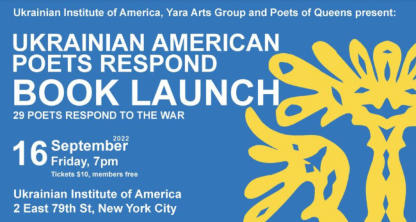

Latest News:

Big thanks to

The Poetry Distillery

for publishing and nominating

my poem

“The Stolen Children”

for the 2025

Pushcart Prize!

* * *

So thrilled to have three poems

included in the stellar collection:

“Shattered!

Artists Inspired by Artists.”

* * *

I’m honored that my poem

“Floodwaters” was published in the

Sunflowers Rising — Poems for

Peace anthology.

* * *

Thanks to Fusion Magazine

for publishing my short story

“Bucha Spring”!

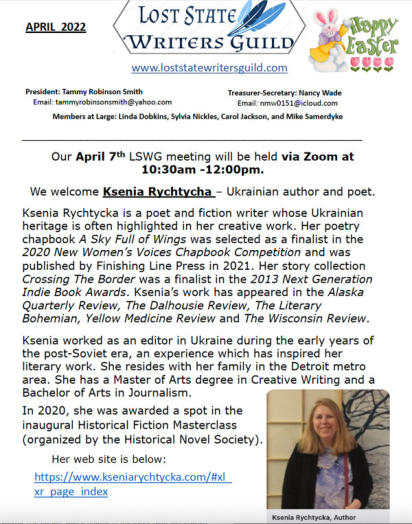

Ksenia Rychtycka

Author | Poet | Editor